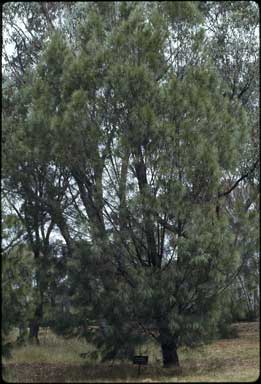

One of the trees common to our local sclerophyll forests is Allocasuarina littoralis, Black Sheoak:

Image: Australian National Botanic Gardens

Image: Australian National Botanic GardensIt superficially resembles a pine, especially given its needle-like "leaves", but closer inspection shows that they are not leaves at all.

The gossamer wing on the right side of the seed is its samara, quite common in plants that use wind for the seed dispersal.

A far more spectacular seed and fruit comes from Hakea sericea, a member of the Proteaceae family. It's remarkable to realise that from these delicate flowers...

Scale: 1mm

In this photo, you can see two sets of the tiny, tooth-shaped leaves on the modified stem. The shape and number of these leaves is key to identifying the species within the genus. The leaves are minute, scarcely visible to the human eye, and clearly it is the stem that is responsible for the plant's photosynthesis. The similarity at first glance to pines is, in fact, an example of convergent evolution. The major difference between pines and members of the family is that while pines are conifers, the family Casuarinaceae are angiosperms: flowering plants.

Allocasuarina littoralis is dioceous, meaning that male and female sexual parts occur on separate trees. Thus at this time of year, roughly half will be in fruit--the females. They flower in spring, with reddish flowers on the females, and dark brown flowers on the males.

After collecting the fruits, I cajoled them to open and release their seed in accordance with the ancient custom: putting them in a paper bag and leaving them on the dashboard of the car for a couple of days. Even in relatively cool weather, this heats them sufficiently for them to open.

Here is a fruit, opened up:

And here is a seed:

Allocasuarina littoralis is dioceous, meaning that male and female sexual parts occur on separate trees. Thus at this time of year, roughly half will be in fruit--the females. They flower in spring, with reddish flowers on the females, and dark brown flowers on the males.

After collecting the fruits, I cajoled them to open and release their seed in accordance with the ancient custom: putting them in a paper bag and leaving them on the dashboard of the car for a couple of days. Even in relatively cool weather, this heats them sufficiently for them to open.

Here is a fruit, opened up:

And here is a seed:

The gossamer wing on the right side of the seed is its samara, quite common in plants that use wind for the seed dispersal.

A far more spectacular seed and fruit comes from Hakea sericea, a member of the Proteaceae family. It's remarkable to realise that from these delicate flowers...

...will develop to become these large, woody fruits...

This fruit has split open, again by means of the car dashboard. The two black seeds are visible inside.

Like the seed of the Allocasuarina, the much larger Hakea seed also has a samara. That the fruit is so large and solid, and in terms of production, energy-expensive, can perhaps be explained by the fruit remaining closed until the shrub dies or until it is consumed by fire. It might have to protect the seeds for many years before it is time for them to germinate. Hakea leaves are perilously prickly and hard. Falling onto one would not be fun.

I'll be germinating the seeds from both species shortly, and will follow their growth and development here. There are few things more satisfying than growing plants that are indigenous to your own region, knowing that they'll fit perfectly into the ecosystem of your garden!

I'll be germinating the seeds from both species shortly, and will follow their growth and development here. There are few things more satisfying than growing plants that are indigenous to your own region, knowing that they'll fit perfectly into the ecosystem of your garden!

Hi Margaret,

ReplyDeleteWhat a great nature reserve to have so close to your home!

I especially liked the top photo with the boulder -showing a complex variety of cracks, erosion pattern and faults in one part, but so massive and smoothly rounded on the top - among the trees and smaller plants.

cheers

Tim in Canberra

Hi Tim,

ReplyDeleteYes, the rocks around here are wonderful. Ancient, magnificent sandstone, full of caves and weathering effects. We're lucky enough to have a sandstone platform in our garden, on which grows an array of local plants, and no weeds at all. (Basically, the thin topsoil is so lacking in nutrients that the only things that can grow are those evolved in such an environment.)

Apart from it being a haven for plants, it's also the highway for the wallabies, brush turkeys and other wildlife to travel across our garden into the National Park behind us. It's a source of endless entertainment!